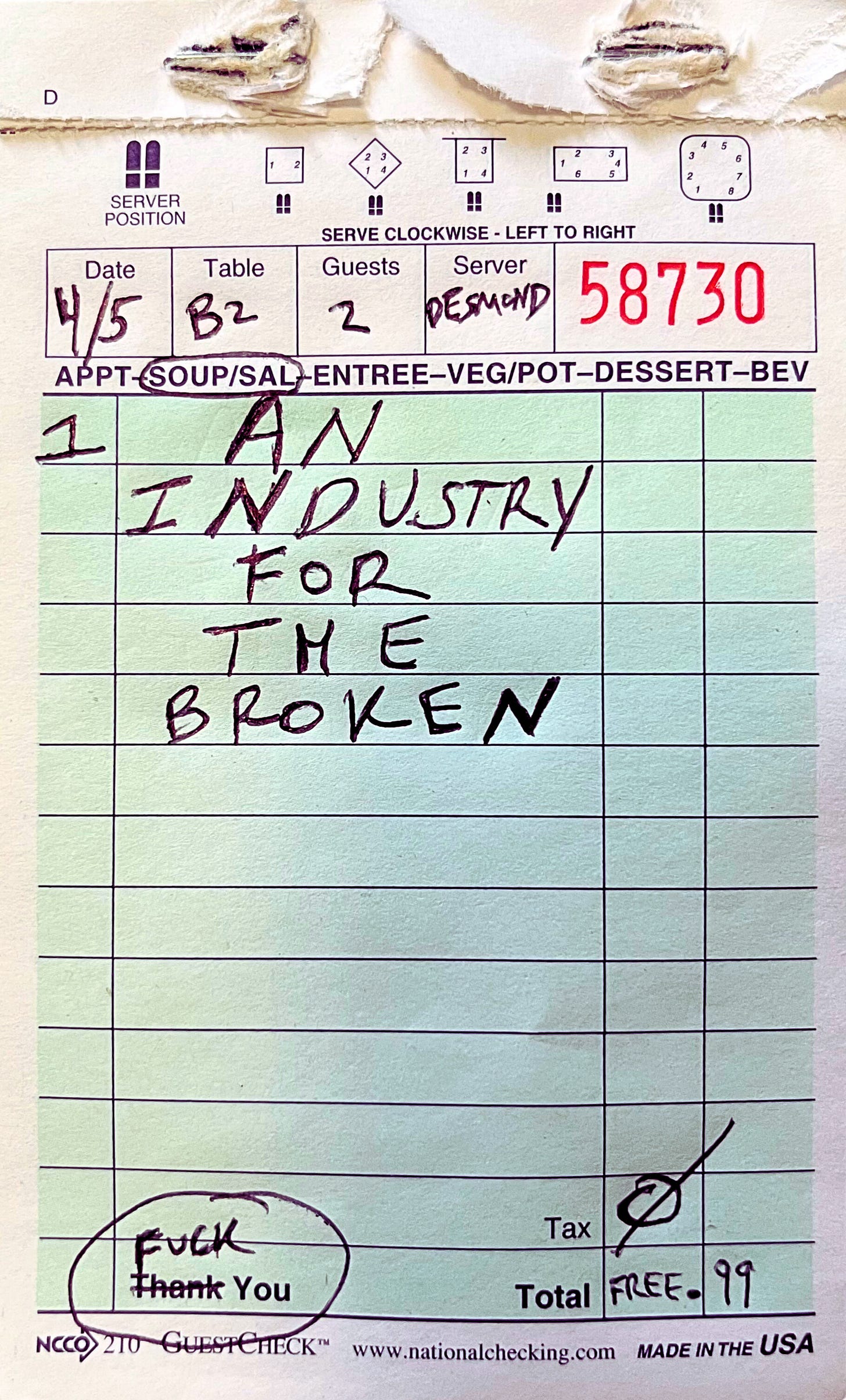

“Restaurants are an industry for the broken. Dealing with the public is an undeclared war. The back of the house is a war by proxy. The floor’s a meandering trench populated by lost children pretending to be adults. The bar’s an eagle’s nest. Every bottle’s an empty shell. No one leaves unscathed.”

(Me, VILE SELF PORTRAITS, “THE VINEYARD,” p. 150)

I was eighteen when I took my first serving job at Napper Tandies in the sad soft suburbs of Massachusetts. A budding booze bag with a feral mop of strawberry-blonde hair. My father knew the owner, so all I had to do was fill out an application and the job was mine. The first few weeks were disastrous. I was perpetually late. And stoned. My voice quavered when I greeted tables. Eye contact was difficult. I dropped plates, pints, forks, knives, trays. Teenage tremors. The fear of newness. Anxiety cuts deeper when you’re young. When you’re older, it’s just another day, another shitstorm to the face.

Back then, I had no tangible goals beyond becoming a great American novelist and seducing many women. Responsibility was just a word, an inconvenient concept my father never shut the fuck up about: "Connah, everyone has a job. It’s a paht’a life, an activity of daily livin’, A-D-L. Ya gutta work hahd, save up ya money, and be a productive memba of society. Can’t sit around on ya ass all day writin’ ya little poems, c’mon. I didn’t raise a loosah, did I?"

He was always an asshole.

Aimlessness is a symptom of youth. For some more than others. I never imagined that nightmarish serving job would turn into my "career." I thought I’d write something brilliant and be the next smarmy cunt forcing a chemical smile next to Jimmy Fuckface on national TV. I wasn’t even writing prose at the time. Just poems. And some of them rhymed. Here’s proof:

The Deterioration Of An Entire Generation Through The Evaporation Of Free Thought Condensation (2011) It all starts with anger, frustration Then your thoughts are captivated by the blaring TV station, It's channel 25, It’s the 5 o'clock news, So let the nice-looking man manipulate your views With his 50-cent smile and his million-dollar suit…

I know. Chinaski’s dirty old bones are rolling in his grave, disgusted. But stay with me. Don’t click away to the endless feed of Substack’s bestselling hacks peddling “wisdom” to dilettantes. I won’t subject you to that ever again.

We all start somewhere.

During my serving shifts at Nappers, I’d watch the bartenders, the way they danced around each other, their indomitable confidence, their unique shakes and stirs, whirs of fluid motion with ceaseless smiles. Not only were they having fun, but they were drinking, too. Heavily. There was a lawlessness about them, a reckless, seductive allure. They were the focal point. The bar wasn’t just a watering hole, it was a stage. I remember thinking: That’s it. That’s what I can do. Something clicked, some primitive part of myself that craved chaos and legendary hangovers.

I approached my manager Melissa and asked, "Hey, can I train behind the bar?" She hated me. I was a walking calamity. Days before, I dropped a Bloody Mary on a woman wearing a white dress. I should’ve been fired, but I wasn’t due to my father’s relationship with the owner. That made her loathe me even more. (I get it. Nepotism’s a fucking plague.) She replied with venom in every word: "I don’t think you’re cut out for bartending, Connor."

So I quit.

Following a week-long drug binge, I tried to kill myself—likely for writing bad poetry. Ate twenty Xanax footballs and cut my wrists, let the blood pour. Lost a few days and woke up in the psych unit of Norwood Hospital. Here’s a Google review of the now-shuttered unit, verbatim:

★☆☆☆☆ If I could give it zero stars, I would! This place is beyond shady! We were not allowed in the dining room at any time. We were not allowed to bring in a purse or cell phone. The Psychiatrist NEVER touched base with me the whole time my mom was there (almost a month!). Near the end of her stay, my sister went to visit and found mom reeking of urine. She took her to the bathroom, and her adult briefs were so wet with urine, you could ring them out! She also had bruises all over her arms! Once, when I asked for someone to take my mother to the bathroom, the CNA showed up and literally brought her there and back in two minutes. She said "I asked her if she had to go, and she said she already went. So, I turned around and brought her back." Seriously?! SHE HAS DEMENTIA!!

I’m not sure what the reviewer is talking about. I had a fantastic stay. Five fucking stars. Zyprexa’s like a SweeTart, and those twenty-one-milligram nicotine patches—chef’s kiss. I’ve never had such real dreams.

Folks flaunt their insanity like a social currency in our "I’M THE FUCKING VICTIM, FORCE FEED ME SYMPATHY, LOOK AT HOW FUCKING FUCKED UP I AM" world. But I didn’t want to talk about it. Nobody else did, either. Certainly not my parents. They’d rather discuss the weekend weather on the Cape or the Sox game.

Not their deteriorating son.

My close "friends" were hesitant around me. Treated me like something foreign. Defective. Broken. Like I wasn’t the person they knew all along. I had become an other. An outlier. Crossed the imaginary line we all draw in our minds. The hometown I’d always subconsciously loved started looking grim. I realized I had two choices: stay and rot or leave and run.

Jim from high school was living in a rented house in Brighton with a few other misfits. When his roommate abruptly left, my father begrudgingly fronted me a month’s rent ($430, Jim and I split a room) and I moved in. Like me, Jim skipped college for the starving artist lifestyle. He landed a minimum-wage job at the Urban Outfitters in Harvard Square—not because he was qualified, but because he wore circulation-cutting jeans and played somber acoustic guitar. One glance at Jimbo and you’d think: This guy’s misunderstood. Some manic pixie dream girl who smells like menthols and flowers must’ve hurt him. But Jim and I were aimless together. We threw house parties and basement shows. Laughed and smiled. Rode the Green Line to nowhere. Funneled cheap liquor. Smoked a twenty-bag daily. Marlboro 27 spliffs. His favorite.

It was a beautiful time. I was alive. I wanted to be alive. I had "friends" and girlfriends. People liked me. They’d call and ask, "Hey man, what’re we doing tonight?"

Then I started eating acid for breakfast and sniffing Percocet for dinner to quell the hallucinations. Then I was shooting dope until my arms were bruised sapphire.

Then I was homeless, breaking into cars to steal change.

With calloused veins.

La ti da.

◆◆◆

Smash cut.

Fast forward two years and one heroin addiction. One arrest. One ruined relationship. One shattered soul. Another suicide attempt. 14,976 cigarettes smoked to the filter. Forty-eight packs of insulin syringes (1/2 inch, 28G, 100 units each).

The rancid erosion of my dignity.

I had just left rehab. Moved into my parents’ apartment on Mission Hill. A remodeled pickle factory. Early sobriety filled me with imbecilic optimism. The blind zealots of AA call it "pink cloud syndrome." I had that terrible type of confidence only young fucks can muster. My father told me, "Connah, if ya don’t havah full-time job by the enda the week, you’re back on the street." Desperate, I applied to every entry-level gig on Craigslist, including a serving position at TGI Fuckdays, A.K.A. Chotchkie’s. The Brigham Circle location was a ten-minute walk from the pickle factory. I stumbled into the interview with a weaponized grin and introduced myself to the general manager, Kevin—a short, insecure twenty-something with patchy stubble and twitchy, shit-brown eyes. He wore a branded button-down (In Here, It’s Always Fuckday!) tucked into baggy dress pants. His voice was that of a nasally child parodying an adult. We were polar opposites—me, the fuck-up in bloom, artfully damaged, and him, a responsible, miserable young man who went to college for business administration and did everything the right way, only to end up managing a rundown corporate chain flush with degenerates. I’m not sure why he liked me, but he did, and he hired me on the spot. Perhaps he saw in me what was missing from his existence: spontaneity. A brazen indifference. Effortless, undeserved arrogance. Plus, I was a pretty bastard at the time.

But time is a vile whore who fucks us all until there’s nothing left but dust.

Back into the trenches I went, eyes wide shut. When I showed up to my first training shift, a familiar face greeted me: "Sup, bitch, whatchu doin’ here? ‘Memba me?" Marvin was another in a long line of high school "friends" I lost contact with after heroin. He was a massive man. Boisterous. Jocular. Six foot four and at least three hundred pounds. With skin darker than my tar-stained lungs. "Looks like it’s you and me, bitch!"

"Marvin, c’mon, you can’t swear so loud," Kevin whined, stationed by the expo window (where plated food is transferred from the kitchen to the servers).

"Sorry, Kev. Don’t worry, I’ll take good care of ‘em, show ‘em the ropes! He’s gon’ learn taday, I’ll tell ya that! Let’s go, bit—"

"Marvin!"

Training with Marvin was easy. He made everything a joke. You can’t take things too seriously in a corporate hellscape like Fuckdays. He was sluggish, both from his size and the blunts he’d face before every shift. I picked up his slack, icing drinks with ease, balancing plates of limp neon-orange chicken wings like a goddamn acrobat, gliding across the skid-marked floor as if it were instinctual. The trauma of heroin addiction had relinquished my trivial fear of human interaction. My innocence. Waking up to a spike will do that. My voice no longer shook when I approached tables. I spoke with command. Ease. "How we doin’, guys? Welcome to Fuckdays! My name’s Connor, I’ll be taking care of you. Can I grab you some drinks to start?" Within a week, I was the best server on the floor.

Which is like saying I was the sharpest person in a room full of slack-jawed dolts. But still. Not bad for a junkbox.

Brigham Circle sits just down the road from Roxbury, Jamaica Plain, Dorchester, and Mattapan (or Murdapan, as we used to call it). Section 8 housing. Bodegas pushing dope next to playgrounds. Drug dealers and users sprawled about littered sidewalks, living and dying in a day. The juxtaposition is brutal—some of the world’s best universities and hospitals are within pissing distance. But Fuckdays didn’t attract doctors, nurses, or scholars. . .

Enter: Endless Fucking Appetizers.

Something only a corporate cunt could invent. Pay ten dollars per person, pick three options from a list of cancerous fried meats and cheeses, and eat until you either projectile vomit or drop dead of a heart attack. Two behemoths would waddle in, order two rounds of endless apps and waters with lemon, take a few boxes to go, pay in exact change, and leave a cataclysm of sauce-soaked napkins and noxious food scraps in their wake. I’d grab the checkbook and dimes, nickels, and pennies would spill to the floor.

And I’d pick them up.

One-by-fucking-one.

I was an alabaster peasant engulfed by ebony pawns. Burrowed deep in the trenches, at war with the poor. Living off their scraps.

But living nonetheless.

Buy my novel here.

As a former waitress and bartender, I felt this. Your way of writing about the not so mediocre past is effective and engaging. Because those little moments lead to the big ones, and I felt like I was in your diary. Thanks for sharing. 🖤

Great writing. Seductively dark.